Most teams bring artificial intelligence into their stack to speed things up, cut routine work, or impress customers with smart features, yet within a few months those tools start doing something else too: they reflect how the company already thinks and behaves. When chatbots, scoring models, or copilots are tuned to match current processes, companies often turn to AI development services to wire everything together, and that is when the “algorithmic mirror” effect shows up most clearly. Instead of a neutral helper, the system starts to echo old habits, gaps in data, and unwritten rules.

This mirror is not a mystical idea. It is simply what happens when rules and historical data are written down in code, then applied at scale. The more decisions a model supports, the easier it becomes to see which customers get attention, which risks are ignored, and which people inside the company have the loudest voice in shaping the training data.

How AI Apps Copy the Way a Company Already Works

Every automated decision hints at a prior human choice — someone picked the target metric, someone decided which records counted as “good” or “bad,” and someone accepted the tradeoff between speed and nuance. Once those choices move into an AI system, they stop feeling negotiable and start looking like neutral logic. However, the system is still only replaying a past view of what matters.

Customer support assistants trained mostly on old tickets will prefer the kinds of answers that helped close cases in the past, even if newer policies focus on long term loyalty instead of fast closure. Hiring tools that rank candidates by similarity to past hires simply encode what the organization already rewarded. As researchers point out in work on artificial intelligence, these tools amplify whatever goals and definitions they receive, whether or not those goals still fit current plans.

That is why early experiments often feel underwhelming. The chatbot repeats stiff email language. The sales assistant nudges teams to chase the same accounts they already know. The code copilot reflects the structure and quirks of the existing codebase.

Blind Spots That Show up When Algorithms Start Making Suggestions

Once a company leans on AI apps every day, certain patterns keep returning in dashboards, prompts, and user complaints. Typical signs of that include:

- Missing or skewed data. The model keeps asking users for information that should already exist, or makes strange guesses for certain regions or customer groups, which usually means those cases were underrepresented or poorly labeled in the data it learned from.

- Frozen definitions of “good.” The system still rates quick replies higher than thoughtful ones, or prioritizes short-term revenue over durable customer relationships, because no one updated the labels and metrics after the business strategy changed.

- Quiet groups that vanish from the radar. Segments such as smaller customers, non-English speakers, or people in newer markets rarely show up in recommendations, since historic data favored bigger, louder, or longer-standing accounts that already had strong records.

- Overconfidence in rankings and scores. People start treating the model’s top suggestion as a final answer rather than a starting point, which hides weak spots such as algorithmic bias or missing context that human reviewers would normally catch.

AI development companies see these patterns across many industries, because the same habits tend to appear whenever data from several systems are stitched together in a hurry. It is the way the “algorithmic mirror” makes invisible tradeoffs visible to everyone who works with the tool.

Turning the Mirror Into a Guide Instead of a Trap

The point is not to blame the model for copying human decisions. The useful move is to treat each AI rollout as an audit of existing practices. When a new assistant behaves in ways that feel unfair, unhelpful, or strangely narrow, it is often reflecting policies or shortcuts that have been around for years.

A good starting point is to look at three areas together:

- Who defines success. Review who set the main goals and labels for the system, and how often those definitions are revisited, so that changes in company priorities do not stay invisible inside old datasets and prompt templates.

- Where humans stay in the loop. Map the moments where staff can question, correct, or override model output, and check whether those people have time, training, and psychological safety to disagree instead of rubber-stamping whatever the system presents.

- How feedback flows back into design. Track which complaints, support tickets, and internal suggestions actually result in changes to data sources, prompts, or model settings, since many teams collect feedback yet rarely turn it into new training examples or updated rules.

This is where a structured AI development firm can help translate messy findings into a clear plan, and partners such as N-iX often support that translation work. However, the company still needs internal owners across legal, product, and operations to argue about tradeoffs and write down the decisions. Without that alignment, even the best-designed tools will keep repeating yesterday’s guesses about what matters.

Keeping humans inside the loop is not only about safety. Research on human-in-the-loop machine learning shows that active review and correction can improve model performance while also building shared understanding of how and why the system behaves as it does. In practice, that means pairing each new feature with logging, review meetings, and clear options for people to say “this output is wrong or harmful” in a structured way.

Final Thought

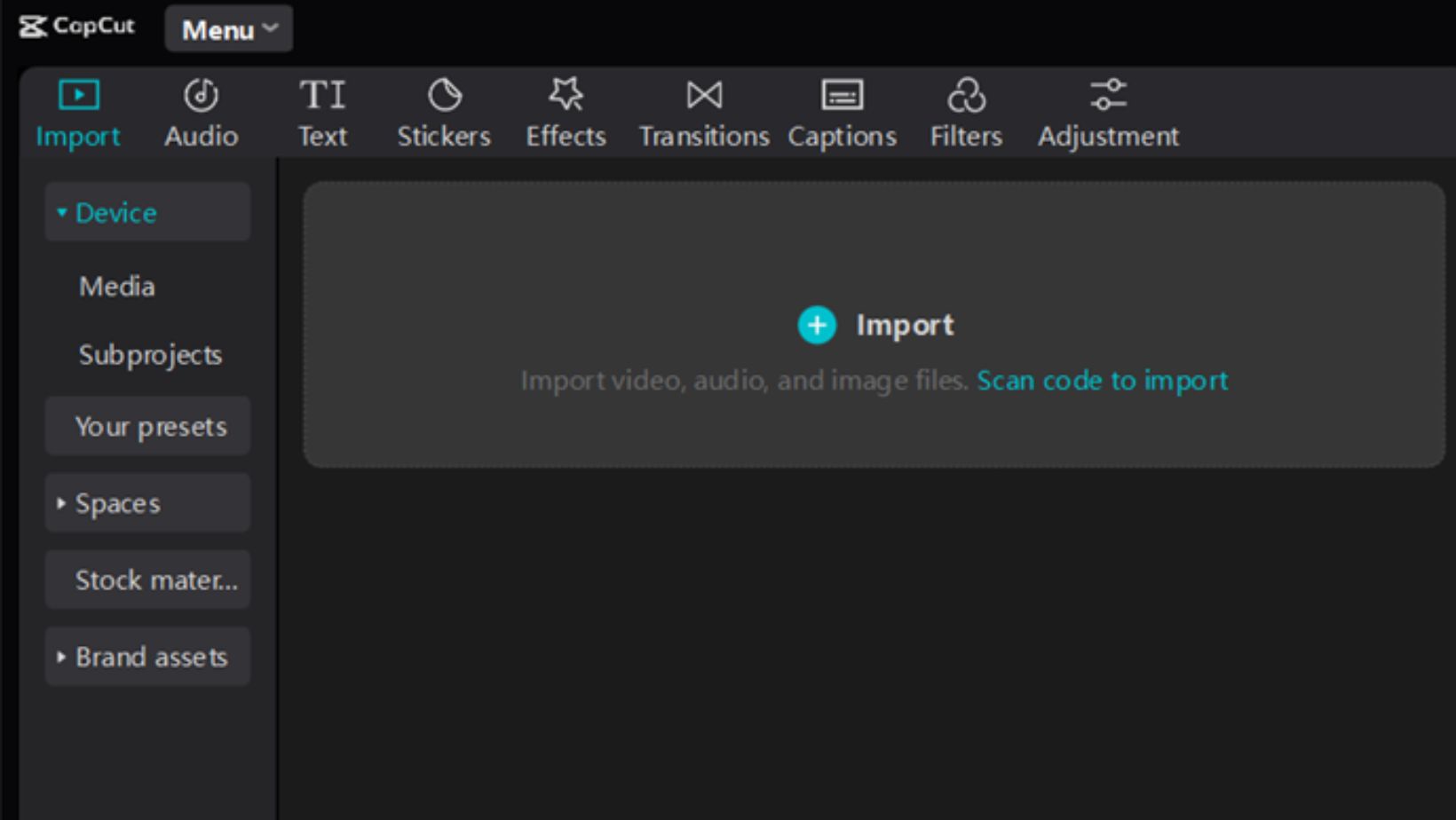

AI apps will continue to spread through everyday work, from drafting emails to scoring leads and supporting hiring choices, and companies will keep turning to AI development agencies to wire those tools into older systems. The question is whether that is treated as a one-time installation or as an ongoing chance to notice blind spots.

When leaders invite teams to study how their AI behaves, instead of treating it as a black box that must be trusted, they get a rare outside view of their own habits. Therefore, the “algorithmic mirror” becomes more than a warning about bias. It turns into a shared practice of asking what kind of company the current data describes, whether that picture is still acceptable, and which small adjustments today would lead to fairer, clearer, and more effective decisions tomorrow.