Ray Caldwell, a pitcher for the Houston Astros, was struck by lightning while pitching in the sixth inning of a game against the Seattle Mariners on May 2nd, 2017. This is his amazing story.

The ray caldwell death is the story of Ray Caldwell, a pitcher for the New York Yankees who was struck by lightning during a game. He survived and finished his game despite being on life support.

Ray Caldwell dons a Cleveland uniform for the first time on August 24, 1919. The weather is scorching hot but clear for the time being, and none of the 20,000 or so spectators at League Park have any clue what they’re about to see. Caldwell will tell a tale of desperation, fear, survival, and redemption over the following two hours.

As he approaches the mound, the audience erupts in applause, and the applause becomes louder as it becomes clear that Caldwell is at his best today. The stakes for the right-hander are well-known among Cleveland fans: The Red Sox had recently waived him, and the pulse of his once-promising career had all but stopped before that day. This is his last breath.

He’d been considered as a transcendent talent five years before, possibly one of the best pitchers of all time, until drinking issues pushed him to the fringes of baseball. In a bid to make the playoffs, Cleveland player/manager Tris Speaker wanted to give Caldwell another opportunity, which seems like a brilliant decision this afternoon.

Caldwell’s 6-foot-2, 190-pound physique has earned him the nickname “Slim” because of the way he uses every ounce of it to throw an above-average fastball and exceptional curve. But he mainly relies on his devastating out pitch, which is one of the greatest spitballs in baseball. The pitch is still legal, and Caldwell has great command against the Philadelphia Athletics on this particular day; the A’s are stranded for two hours, managing just four singles and a walk in eight innings.

But suddenly, off Lake Erie, the clouds sweep in quickly. Cleveland’s players, who have become used to the lake-effect weather mood swings, take their positions in the hopes of getting three more outs before the heavens open up completely.

As the rain increases up, he hastily toes the rubber. To start the inning, he gets two simple infield popouts. There’s one more to go. The wind is howling now, and the storm has descended onto the field.

A light from the sky crashes down into the center of the field just as he gets set. Ray Chapman, the shortstop, feels a shock of electricity go down his leg, and the force of the lightning forces players to dive for cover. Cleveland catcher Steve O’Neill later recalls of his metal mask, “I pulled it off and hurled it as far as I could.” “I didn’t want any bolts to be drawn to me.”

Everyone glances around five seconds after the bolt strikes the ground. The position players for the Indians are all OK, but their newest colleague is not. Caldwell is down on his back on the mound, arms extended wide. The bolt of lightning had struck him square in the face.

Players rush to Caldwell, but the first to touch him jumps into the air, claiming to have been electrocuted by Caldwell’s prone body.

As a result, everyone takes a step back and simply looks. Caldwell’s chest is burning from the burn caused by the bolt. Nobody dares to touch him because they’re afraid.

Is Ray Caldwell dead, they all wonder?

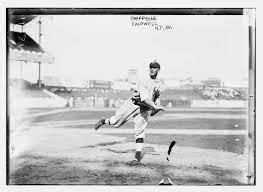

Ray Caldwell, at the age of 25, finally figured out how to control his immense talents, capturing national notice with an 18-9 record and 1.94 ERA for the New York Yankees. Photographs from the Bain News Service/Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington

Caldwell had a spectacular talent from the moment he picked up a baseball, and he had a penchant for landing in impossible-to-believe circumstances. Caldwell’s parents divorced at a period when divorce was uncommon. His father was a preacher who went to Europe, and historians aren’t clear how close the two were. Caldwell’s mother remarried, to a telegraph operator, and he grew up idolizing his stepfather’s work. Caldwell spent much of his offseasons as a telegraph operator for railways, even after he reached the big leagues.

Caldwell batted left-handed and pitched right-handed, and his status skyrocketed from the moment he joined with a semipro club as a 20-year-old. He pitched for the New York Highlanders, who became the Yankees a few years later, two years later, in 1910. In his first four years, he finished 32-38 while playing for mediocre New York clubs. Caldwell’s run support was historically poor, historians say, even in the dead ball era — at one point, he pitched 52 straight scoreless innings… in which his teammates didn’t score, either.

Caldwell had finally learnt to control his abilities by 1914, when he was 25 years old. For New York, he finished 18-9 with a 1.94 ERA, and he was hailed as an up-and-coming star in the coming years. Caldwell has been compared to Christy Mathewson and Walter Johnson by Grantland Rice. In fact, when both Johnson and Caldwell were in their primes, Washington contemplated moving Johnson for Caldwell, but the American League president at the time cautioned the club that it would be a terrible trade because Caldwell had too much promise. “Caldwell looked like he might be an all-time great early in his career,” says John McMurray, head of the Society for American Baseball Research’s dead ball period committee. “He had that degree of ability.”

Caldwell’s wheels started to come off about that time. He had serious drinking problems, which were referred to as “irregular habits” or “outbreaks of misconduct” by newspaper columnists at the time. For his alcohol addiction, he’d been fined, suspended, and released many times. Bill Donovan, the manager of the New York Yankees, became so enraged that he fined Caldwell and suspended him for two weeks, which grew into six months when Caldwell refused to return. Nobody knew where he went, not even his relatives. Caldwell reappeared the following March, and it was subsequently revealed that he’d gone to Panama and threw for the remainder of his sentence under an assumed identity.

Ray Caldwell was a thorn in the side. The Yankees re-signed him for the 1917 and 1918 seasons, but his off-field problems became so severe that the club decided to employ two detectives to follow him around 24 hours a day. The Yankees gave up and released him after he repeatedly managed to slide his tail.

In 1919, he joined with Boston and pitched for three months, going 7-4 with a 3.96 ERA. On road trips, the Red Sox strangely put Caldwell in the same room with Babe Ruth, a 24-year-old superstar with a propensity for “outbreaks of disobedience.” Caldwell was released in early August when the club soon recognized the combination was a mistake.

Caldwell would have signed just about any deal placed in front of him when Speaker called him a few weeks later. And it’s a good thing, too, since Cleveland gave him one of the most strange contracts in baseball history, according to historians.

Caldwell was supposed to pitch and then go get plastered on game days, according to the contract. Caldwell was puzzled by the deal, according to historian Franklin Lewis in his book “The Cleveland Indians.”

Caldwell glanced over the paper and remarked, “You missed out one word, Tris.” “The word not has been omitted out where it says I have to get drunk after every game. It should say, “I am not to get inebriated.””

Speaker gave a warm grin. “No, it says you’re supposed to become intoxicated.”

Caldwell had to follow a fairly precise weekly routine, according to Speaker. On game days, he’d pitch before doing his obligatory drinking. He was therefore free to sleep off his hangover instead of going to the ballgame the following day. Speaker, on the other hand, urged him to be at the stadium early the next day to do as many wind sprints as the manager felt he required. Caldwell was required to throw batting practice three days following each start. Pitch, drink, sleep, run, take your blood pressure, and repeat.

Historians think Speaker, a real innovator as a player/manager, believed Caldwell’s skill was worth the unusual risk, and that by allowing him a free pass day of unrestricted drinking, Caldwell would be able to stay on track for the other three days of a pitching cycle. “I’ve never heard of anything like it,” says Steve Steinberg, a dead ball period specialist. “And I can’t think of anybody now giving a bargain like that.”

Caldwell shrugged his shoulders. He replied, “OK, I’ll sign.”

Caldwell hit the mound five days later, eager to make an impact.

On April 5, 1913, Caldwell throws the first pitch at Ebbets Field. Photographs from the Bain News Service/Prints and Photographs Division of the Library of Congress

Caldwell, 31, begins moaning and climbs back to his knees, then his feet, just about the time everyone on the field is ready to declare him dead.

Teammates ecstatically applaud, but everyone maintains their distance from the man whose chest had just caught fire. They offer to accompany him to the hospital as he leaves the field. Caldwell, on the other hand, is skeptical.

He adds, “I have one more out to get.”

He’s persistent enough that Speaker finally walks back to center field and allows him to remain on the mound to complete his game. “Give me the dangling ball and turn me toward the plate,” Caldwell says to Chapman.

Umpires As players return to their places, Brick Owens and Billy Evans stay surrounded around the mound for a minute. The shortstop for A is Jumping Joe Dugan sits at the plate, waiting for the umpires to indicate that the game may resume. Owens and Evans finally exchange a shrug and gaze at each other. They tell you to “play ball.”

The fans had dispersed in the chaos of the lightning strike, which is thought to have fragmented, struck Caldwell, and also impacted the press box, sending people fleeing in all directions. Many people leave the game right away, but those who are courageous enough to stay there return to their seats.

Dugan takes a strong cut on Caldwell’s first pitch, hitting on a hard grounder to Willie Gardner at third base, who can’t handle it cleanly. He smacks it to the ground in front of him, catches it, and throws it to first base just in time. Ray Caldwell escaped a lightning strike and just completed a complete-game victory in the most important game of his life, and the Cleveland fans still in attendance are as surprised as the players on the field.

That day, Evans even talks to the press. “We could all feel the tingling of the electric shock going through our systems,” he adds, referring to his legs.

Caldwell is brief with the reporters after the incident: “Felt like someone came up with a board and whacked me on the top of the head and knocked me down,” he tells the Cleveland Plain Dealer.

It’s impossible to say if Caldwell was rushing to the bar after one of baseball’s most spectacular pitching performances, but by all accounts, he completed his contract duties in 1919.

Caldwell in the year 1913. He’d tell the Cleveland Plain Dealer six years later, after getting struck by lightning on the mound, that it “felt like someone came up with a board and whacked me on the top of the head and knocked me down.” Photographs from the Bain News Service/Prints and Photographs Division of the Library of Congress

CERTAINLY, THIS SOUNDS LIKE A CENTURY-OLD MYTH. Is it possible for a guy to withstand a lightning strike and then endure another?

Yes, yes, yes, yes, yes, yes, yes, yes, yeah, yes

One of nature’s weirdest occurrences is lightning. Because so many spectacular pictures of strikes seem to show the bolt shooting up from the ground, people often wonder whether lightning strikes from the sky down or from the ground up. The reality is that lightning may strike from both above and below.

Consider how Wi-Fi works. Lightning, like Wi-Fi, needs a ground partner to connect to. A thunderstorm’s charge shoots downward, but it must find an opposing charge from the earth, known as a “upward leader.” Many strikes find many partners in the same region, distributing the charge (between 100 million and 1 billion volts of electricity) to whatever upward leaders it can find, such as flagpoles, trees, or, yes, humans. That’s why many depictions of lightning strikes show splintering rather than a single massive bolt, with some resembling one arm reaching up from the ground and the other reaching up from the sky.

Caldwell’s lightning hit, according to lightning specialist John Jensenius, was most likely an upward leader strike. Direct hits are uncommon, particularly in crowded areas like a city’s baseball stadium. That implies that part of the voltage from the bolt that struck Caldwell was likely absorbed by other nearby objects. “Those types of lightning strikes don’t kill people,” says Jensenius, a veteran National Weather Service employee known as Dr. Lightning. “However, I doubt they go up and get the last out of a baseball game.”

Except for the players’ claim that they touched Caldwell and felt a shock, Jensenius believes most of the lightning-specific facts are accurate. Jensenius asserts, “The human body is not a battery.” “It is incapable of conducting electricity.”

He also believes that rain and perspiration increased Caldwell’s chances of becoming a lightning receiver. What if the pitcher was coated in saliva and other liquids from the baseballs he was treating? Dr. Lightning replies, “I’m not sure that would make much of a difference.”

He takes a breath and stops for a moment. He replies, “I suppose if he was coated in a lot of spit and other liquids.” “Did pitchers actually do that back then?” you may wonder.

Yes, yes, yes, yes, yes, yes, yes, yes, yes, yes, yes, yes

Baseball was engaged in an argument that sounded very similar to the one we’re discussing now by 1919. Pitchers had grown too dominating, with the capacity to alter the game by making the ball do strange things. They had many other advantages back then, like as spacious stadiums and managers who preferred little ball, but nothing stopped offense like pitchers’ ability to manipulate baseballs.

Scuffing, slashing, spitting, sanding one side of the ball repeatedly, you name it: it’s all allowed. Caldwell never disclosed his unique spitball formula, although spit combined with slippery elm tree bark was the most common mixture at the time. Pitchers sucked on the elm bark, resulting in spit with an additional layer of gooeyness. Other common additives were petroleum jelly, tobacco juice, licorice, and even dirt.

Caldwell and the other spit wizards could work on a ball for almost the whole game without incurring any penalties. It was prohibited for spectators to retain foul balls or home runs back then since owners complained so much about having to pay for additional baseballs. (On average, two balls are used each game.)

However, as fan dissatisfaction with the lack of offense grew, owners tried to outlaw the spitball in 1920. Spitballers, on the other hand, campaigned hard and persuaded owners to approve a perplexing compromise: the remaining 17 spitballers were grandfathered in beginning in 1921. Nobody else could fix baseballs like they could.

“There are some uncanny similarities to the current debate,” adds Steinberg, who has written extensively about the dead ball period, particularly Ray Caldwell. “Is baseball going to destroy the careers of some present superstars by changing or enforcing new rules? Back then, owners had to make a tough choice. Should they stick to what they’ve previously said or give in to the pressure?”

The proprietors were able to accomplish both at the time.

Caldwell’s performance began to deteriorate a few years following his lightning-strike season. He moved around the minors and the bullpen until retiring in 1933. National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

Ray Caldwell’s comeback gets off to a blazing start in Cleveland in 1919.

Caldwell adds to his legend by pitching a no-hitter against the Yankees three weeks after being struck by lightning and miraculously completing the game. He ends the 1919 season with a 5-1 record and a 1.71 ERA, and the Indians have the pieces in place for a possible playoff run in 1920.

He and fellow spitballer Stan Coveleski deliver a devastating 1-2 blow to Cleveland in 1920. Cleveland defeats the Brooklyn Robins for their first World Series championship, going 44-24 with 46 full games.

Caldwell, on the other hand, begins to deteriorate the next year. Speaker puts him in the bullpen, but the manager subsequently suspends Caldwell for “alcohol problems,” according to local media. Later that year, the team releases him. “Whether it was maturity, booze, or anything else, he couldn’t quite put it together,” says Jeremy Feador, team historian. “However, he had that incredible last go in Cleveland.”

Caldwell spends another 12 years in the lower leagues, winning 140 games and earning a decent life on the outskirts of professional baseball. He’s a 43-year-old grandfather on his fourth marriage by the time he gets to the Mississippi Valley League’s Keokuk, Iowa. He has made $49,400 from baseball when he quits for good in 1933. In his older years, he runs his farm, works as a telegrapher, teaches baseball clinics for youngsters, and works as a casino greeter.

Caldwell died in 1967, but he is still a popular topic among baseball historians. He had a crazy career that included 292 victories in 4,400 innings of major and minor league baseball, a short time as Babe Ruth’s bunkmate, the oddest contract in MLB history, a half-year disappearance to Central America, and, of course, one spectacular lightning strike. Steinberg describes him as “probably one of the most colorful, complex people I’ve ever written about.” “And for a few years, he was virtually untouchable.”

On their way to the 1920 World Series, Caldwell and fellow spitballer Stan Coveleski were a deadly 1-2 punch for Cleveland. National Press Photographic Service/Library of Congress/F.A. Flowers Co.

ONE OF FEADOR’S FAVORITE DUTIES AS CINCINNATI’S TEAM Historian DURING NON-PANDEMIC TIMES is conducting road performances. He’s invited to libraries, museums, and a few of historical societies. His talks typically last 45 minutes, followed by 15 minutes of questions and answers. Although the audience is older, Feador is often startled by the amount of 10-year-old baseball enthusiasts who stare at him.

He tells the story of Cleveland baseball chronologically, beginning in 1869 and progressing through the bleak days of the late 1800s, when the team went 20-134 in 1899 after brothers Frank and Stanley Robison effectively sent all of Cleveland’s best players to their other team, the St. Louis Cardinals, in order to boost attendance there.

That offers him a dramatic run-up to the golden days of 1919 and 1920, when Speaker was establishing himself as a legend whose out-of-the-box thinking aided in the formation of a strange, wonderful squad around him. He is recognized with being the first manager to experiment with platooning players, and his choice to put Smoky Joe Wood, a broken-down pitcher, in the outfield was unheard of at the time.

Feador gets to the 1920 World Series championship around 10 minutes into his presentation, but he keeps Ray Caldwell in his back pocket until the nine-minute mark, just in case anyone’s attention starts to wander. That’s when he takes 60 seconds to talk about Speaker’s hazardous effort to resurrect Caldwell’s career, the strange contract he signed, the great potential that never fully materialized, and the spitball’s popularity at the time.

Then he slams it down on their heads: “You strike ’em with that lightning bolt, and it adds some spice to the proceedings. That’s the sort of tale that piques children’s interest in history.”

People sit up straight as their jaws hit the floor, and Feador rides that wave into the magnificent 1920 World Series season. Then he goes through the history of baseball in Cleveland. He devotes a significant amount of attention to outstanding accomplishments and does not shy away from addressing the franchise’s numerous name changes, particularly the often criticized history of adopting “Indians” as a team name. He’s excited to discuss the recently announced move to Guardians.

Everyone generally gets up and claps when Feador finishes. The hands then begin to raise with inquiries. Fans are always interested in learning more about how the club might have moved Shoeless Joe Jackson to the White Sox during his peak, as well as any amazing Jim Thome or Kenny Lofton tales he may have.

Then someone will eventually grab the microphone and say something along the lines of, “The lightning strike man… did that really happen?”

Feador usually chuckles and responds, “Yes, it did.” He speaks about how many journalists wrote about the game just after it happened, and how players from both Philadelphia and Cleveland spoke about Slim Caldwell’s scorching chest for decades.

And he often concludes his response by citing the plaque he helped create, which sits down the third-base line at Progressive Field and reads, “Caldwell made arguably the most electrifying debut in Cleveland Indians history.”

The texas ranger pitcher struck by lightning is a short article about Ray Caldwell, who was playing for the Texas Rangers when he was hit by lightning.

Related Tags

- ray caldwell cause of death

- ray caldwell obituary

- ray caldwell lightning video

- ray caldwell lightning strike

- ray caldwell jersey